We Know They're Evil Because They Watch Voyager or, Some Scary Thoughts About Being a Genre Fan

Hamza and Yehat are two over-educated, under-appreciated twentysomethings working dead-end jobs and waiting for their lives to start. When Hamza meets Sherem, who is beautiful, smart and completely interested in him, he thinks his luck has finally changed. What he doesn't know is that Sherem has an agenda, that she's been looking for him for a long time, and that before the week is out he and Yehat will hold the fate of the world in their hands.

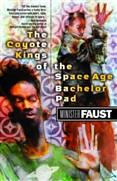

You've read this book before, right? And seen the film and watched the TV series and read the comic book? Well, so have Hamza and Yehat, which is what makes Minister Faust's (the pen name of Malcolm Azania) The Coyote Kings of the Space-Age Bachelor Pad such a hoot (apart from the fact that Faust is a good writer with an excellent ear for narrative voice and a knack for writing crackling plot). Faust faces the hoariness of his plot head-on in a neat meta-fictional trick by making Hamza and Yehat uber-fanboys, armed with stacks of comic books and an encyclopedic knowledge of Star Trek trivia. They're living out a science-fiction geek's dream, and they know it, and they're quoting Obi-Wan Kenobi as they do it. Faust even introduces each character with a D&D stats card, including their 'genre alignment' (the good guys like Babylon 5 and Deep Space Nine, the bad guys like Star Trek: Voyager).

Even a casual genre fan, however, will very quickly notice that Coyote Kings takes place in the mid-90s. Several reviewers have wondered why Faust chose to set his story a decade ago, but his reasons are obvious when you look at the acknowledgment page. Faust was already writing Coyote Kings (then in screenplay format) back in 1996, when his pop-culture references were contemporary. Clearly then, moving the story a decade forward would have been a herculean task when you consider how many of those references (and how much of Hamza and Yehat's personalities and opinions) would have had to be altered.

Think about it. A mere ten year shift would have made Coyote Kings a completely different book. Not because for Hamza and Yehat, if they are even aware of it, the internet is a small club of a few thousands, and not even because the current political situation would certainly have a serious impact on the lives of two anti-establishment youths of Arab descent, but because the genre geek of 1995 is so different from the genre geek of 2005.

These are just a few of the things that Hamza and Yehat don't know:

They have only an inkling of how low Star Trek is going to sink. They don't know that it's going to go from the definitive SF show to the equivalent of an embarrassing older relative who has to be kept in the back room when there's company.

They don't know that Babylon 5 will squander the promise of its earlier years with a terrible final season, some execrable TV movies and a deeply embarrassing spin-off.

They haven't yet given their hearts to a quirky, eerie FOX show about the paranormal, only to watch it blast into the mainstream, spawn dozens of imitators, spiral into a parody of its former self, break the heart of everyone who ever loved it and go down in flames, all in the space of a few years.

A new Star Wars movie is nothing but a rumor to them, and they have no idea how much they're going to wish it had stayed that way.

They don't know that it's possible to make good films out of The Lord of the Rings.

They've never seen The Matrix.

So, if Hamza and Yehat seem this quaint and out-of-touch to readers in 2005, it stands to reason that in 2015, genre geeks will be thinking the same thing about me in 2005. And this matters because for Hamza and Yehat, and for people like them, 'genre affiliation' doesn't just mean which movies and TV shows they like. They are the stories to which the random occurrences of their existence are set, the lens through which they view the world. One can argue that Hamza saves the world because of his awareness of the ways in which his story parallels Star Wars and a dozen other genre narratives. By recognizing that he's playing the Luke Skywalker role, Hamza becomes Luke Skywalker.

Which is overblown and not really relevant to our everyday lives, unless one of you happens to be contacted by a beautiful desert sorceress. But the fact remains that in our commercial society, the things we like inform and affect the people we are. Jane Austen has been a recognized genius for 200 years. Superman has existed for 70. What does it mean when your personal cultural landscape has a shelf life of less than a decade?

Comments

But when you have people whose personal identity is so wrapped up in their cultural preferences, like the characters in this book, and when those cultural preferences are so ephemeral, you have to start wondering what's left of the people themselves.

Which troubles me because, although it's not to the extent that we see in the book, I also define myself by the things (books, movies, television shows) that I like.

Just what it meant to Jane Austen's contemporaries. The cultural landscape has always had a short half-life. Most stuff comes and goes, some stuff fades more slowly, other stuff lasts for centuries and you have to buy annotated versions that explain all the long-dead cultural references.

I'll post relevant news of the sort on THE BRO-LOG at ministerfaust.blogspot.com.

Best wishes,

Minister Faust

Christ. The worst thing about the noughties was the way that geek culture grew increasingly, pointlessly self-satisfied and self-referential... Fans really do seem to lap up portraiture, don't they?

Post a Comment