Recent Comics: Why Don't You Love Me? by Paul B. Rainey

I've written before about the "it's really good" problem—how to review, and direct audiences towards, a work that is simply gangbusters on every level, and seems to offer no access point for the reviewer wishing to praise it. The ecstatic reviews that persuaded me to pick up a copy of Paul B. Rainey's graphic novel Why Don't You Love Me?—the first great 2023 publication I've read this year, and already very likely to make my list of the year's best books—seemed to uniformly suffer from a subset of this problem: how to praise something exceptional without saying too much about it? Guardian reviewer Rachel Cooke wondered: "Will readers stick with [Why Don't You Love Me?] long enough to reach the twist that makes the effort of reading its first half worthwhile? I can't be sure that everyone will – and yet, I must not spoil this twist, even in the cause of encouragement."

I demur a little from Cooke's concern. Why Don't You Love Me? has a tremendous—in both senses of the word—twist around its midpoint, which lands the book firmly in the realm of science fiction, and which I will do my best to avoid spoiling. But to me what makes the book remarkable is what comes both before and after this moment. It's clear almost from the first page that something more is going on here than initially appears. The pleasure of reading comes not only from figuring out what that something is, but, once you've done so, from gaining a new understanding of the path that led to that realization.

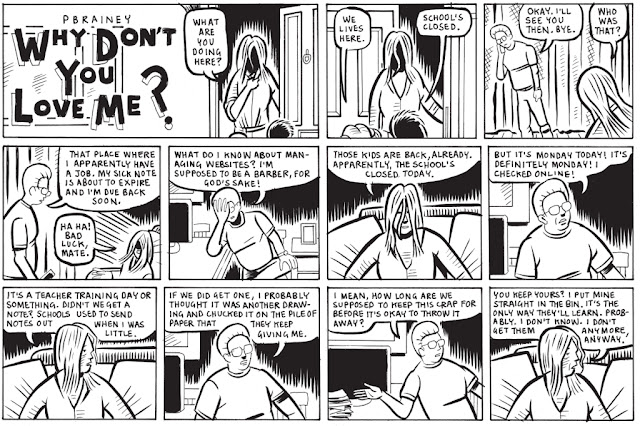

Right from the start, Why Don't You Love Me? sends mixed signals to readers about the kind of comic, and story, it is. The book is presented as a compilation of newspaper strips, originally published on Rainey's website, but hewing very closely to the rigid format of the mainstream funny pages. Each page has three rows of panels, with the top row made up of a large title panel followed by two potential throwaways, and two additional rows with an almost uniform box format. Each page describes a single vignette in the protagonists' lives, and culminates in a punchline. But the style of the art puts one more in mind of subversive, indie comics—thick black lines depicting simplified interior scenes, deliberately unpretty characters, and a lot of emphasis on the accouterments of vice like cigarettes, empty alcohol bottles, or distracting TV and computer screens. The punchlines are more often bleak or gross rather than funny.

Even this gesturing at a familiar style, however, obscures something entirely different. To begin with, Why Don't You Love Me? feels like yet another entry in the very well-populated subgenre of indie comics about how awful middle class suburban life is, and how the people who live that life are constantly seeking to fill the void in their souls with TV, substance abuse, and inappropriate sex. Our heroes are Mark and Claire, a suburban couple with two small children who seem to hate their lives and each other. Claire is barely functional, regularly drinking herself into a stupor and flying into a rage when asked to participate in the running of the household. Mark puts on a more normal front, but inwardly he's flailing, utterly at sea both at home and at work. Neither one seems particularly committed to their marriage vows—Mark flirts with a woman he meets on the long dog walks he takes to get away from his family, and Claire briefly emerges from her drunken haze and starts playing the role of a devoted parent when she meets the attractive father of one of her daughter's friends. Otherwise, the two are wildly neglectful parents, constantly shocked to realize that they're expected to keep their children fed, clean, and in school.

|

| Excerpt from Why Don't You Love Me? by Paul B. Rainey, Drawn & Quarterly 2023 |

There's a similar move here to the one deployed so successfully in the first season of The Good Place, where behavior that would normally be horrifying and even criminal, such as Mark repeatedly forgetting his son's name or Claire sending her grade-school-aged children to the shop to buy alcohol and cigarettes, is normalized because it's assumed to fall within the tropes of a comedic format. But right from the start, Rainey establishes that this isn't entirely what's going on. "Christ! Do you mean all this might be real?" Claire asks Mark in the book's first page, and very quickly it becomes clear that the two aren't simply forgetful or neglectful, but genuinely ignorant. Mark has no idea how to do his job as a website designer and keeps complaining that he's actually a barber. Claire doesn't remember her friends' names and remarks to her mother that she'd hoped her deceased father would be alive. It very quickly becomes obvious that the reason the two are so incapable of functioning as a couple isn't that they're estranged, but actual strangers.

Beyond this general impression, there aren't a lot of hints in this part of the book as to what might actually be happening. Which, we eventually realize, puts us in a similar headspace to Mark and Claire, who have experienced some sort of rupture that they are at a loss to even define, much less explain. Even the major twist at the book's midpoint doesn't really answer our questions. It is, however, a jumping-off point to a careful working out of the book's premise that takes up much of its latter half. Eventually, Rainey reveals a thought-out, shocking SFnal McGuffin which is both enormously satisfying when you finally understand it, and gobsmacking when you realize what it spells out for our heroes. (It also makes Why Don't You Love Me? a pleasure to reread, as certain implications that are never spelled out become clearer on a second pass.)

Still, what's most interesting about this part of the book is the way it makes you reevaluate what came before, seeing it not as a gag about marital dissatisfaction, but as an extreme trauma response. In the second half of the book, the circumstances of Mark and Claire's lives change dramatically, giving them space to not only understand what has happened to them, but to grapple with how they behaved in the initial shock of their lives being so thoroughly disrupted. Not all of these stories are particularly dramatic. Claire gets a rather satisfying storyline about learning to stand up to an abusive boss, while Mark debates between the old dreams of his teenage years, and new dreams triggered by his recent experiences. Eventually, they reconnect and are able to forge a new, more honest relationship—one that is completely unromantic, but also the most meaningful bond they have in their lives.

One possible reading of Why Don't You Love Me? is as a metaphor for how depression and mental illness can render us strangers in our own lives, and how in their aftermath we may find ourselves struggling to make amends to the people we failed while in their grip. I think there's a lot of truth to this reading, which gets at at least some of what Rainey is trying to do. But to me, the SFnal component of the book is not merely an allegory, but fundamental to its story, which is about how people cope with having been roped into a science fiction narrative, and how they respond to their own response.

Mark and Claire have both experienced something otherworldly, and this causes them to reevaluate not just their lives, but how they want to live in the future, even under the threat of more SFnal shenanigans. Much of the couple's emotional grappling in the book's second half is about understanding why they treated each other so badly in its first, and in particular, acknowledging how they mistreated their children. It's impossible to say more without really venturing into spoiler territory, but what Why Don't You Love Me? becomes by its end is a deeply compassionate story about ordinary people learning to cope with the unimaginable, finding solace in the most unexpected of places, and figuring out how, even in the face of complete upheaval, to keep going.

Comments

Post a Comment