Recent Reading Roundup 33

The last recent reading roundup chronicled several months of slow reading. This one covers several weeks of fast reading (a period that also included the Clarke shortlist, reviewed elsewhere). There are several books here that I would have liked to write full-length reviews of, but I read them in such quick succession with several others that any chance of disentangling my thoughts enough for that is now lost. Here, then, are some shorter reactions.

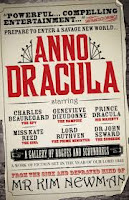

- Anno Dracula by Kim Newman - Newman's much-loved vampire novel, originally published in 1992 and reissued, with a snazzy new cover design, a few years ago, has a crackerjack premise that is simultaneously the best and worst thing about it. Best simply because it's so much fun: Newman posits a world in which not only do the historical and literary figures of the Victorian

era rub shoulders--in which Fredrick Abberline serves on the same police force as Inspector Lestrade, for instance--but the ending of Bram Stoker's Dracula is radically altered. In this world, Van Helsing and his allies failed to defeat the Count, who cemented his hold on England by seducing and turning Queen Victoria. When the story opens, a few years later, vampirism is openly acknowledged and running rampant. The rich turn in order to curry favor with the vampire ruling class, while the poor are turned as a result of predation, and often starve because of it. Newman does a good job of folding the supernatural into Victorian poverty and misery--in the novel's world, a person can turn into a vampire if they're drunk from too often, so East End prostitutes who open their veins to their customers can find themselves turning, cut off from that income stream just as they develop a new thirst for blood that they can't afford to slake. Being a vampire, in this setting, isn't a ticket to power and control as it is in other stories, simply because there are so many vampires, and the privilege of the rich and powerful still applies. This is still a world of law, even if that law is unfair and exploitative--none of the newly-minted poor vampires, for example, are running wild feeding off their social superiors, no more than the real Victorian London played host to a class war--and Dracula's influence is merely exacerbating the inequality that ran rampant in Victorian London.

era rub shoulders--in which Fredrick Abberline serves on the same police force as Inspector Lestrade, for instance--but the ending of Bram Stoker's Dracula is radically altered. In this world, Van Helsing and his allies failed to defeat the Count, who cemented his hold on England by seducing and turning Queen Victoria. When the story opens, a few years later, vampirism is openly acknowledged and running rampant. The rich turn in order to curry favor with the vampire ruling class, while the poor are turned as a result of predation, and often starve because of it. Newman does a good job of folding the supernatural into Victorian poverty and misery--in the novel's world, a person can turn into a vampire if they're drunk from too often, so East End prostitutes who open their veins to their customers can find themselves turning, cut off from that income stream just as they develop a new thirst for blood that they can't afford to slake. Being a vampire, in this setting, isn't a ticket to power and control as it is in other stories, simply because there are so many vampires, and the privilege of the rich and powerful still applies. This is still a world of law, even if that law is unfair and exploitative--none of the newly-minted poor vampires, for example, are running wild feeding off their social superiors, no more than the real Victorian London played host to a class war--and Dracula's influence is merely exacerbating the inequality that ran rampant in Victorian London.

This intricate worldbuilding also feels like the book's greatest weakness, however, because Newman often seems not to be interested in anything else, and especially not in a plot. Anno Dracula was expanded from a novella, "Red Reign," in which one of the defeated characters from Dracula turns out to be Jack the Ripper. But in doing so Newman doesn't seem to have expanded or complicated the story, so his characters--Charles Beauregard, a proto-James Bond employed by the Diogenes Club, and Geneviève Dieudonné, a vampire not of Dracula's line who is trying to alleviate the suffering he's brought to London--spend most of the novel in a holding pattern. The readers find out who the Ripper is in the novel's prologue, but the characters don't even seem to be working hard at their investigation until a few chapters from book's end, and the actual conclusion, exciting as it is, feels disconnected from the novel's action, most of which seems to exist mainly so Newman can introduce characters who will recur in Anno Dracula's many sequels (two of which have already been published, with another coming later this year). It's tempting to say that Anno Dracula has such a great premise that you wish someone had done something better with it, but that's obviously the thinking that got Newman to expand the original novella to begin with, and the result is a fascinating world and a lackluster story, so maybe keeping it short and sweet was the way to go.

- Child of Light by Muriel Sparks - The chapter on Frankenstein in The Madwoman in the Attic left me curious to find out more about Mary Shelley, and though I'm not quite sure who pointed me at Muriel Sparks's biography (originally published

in 1951, revised and republished in 1987), I'm glad that it's the one I chose, and not just because of this recent article in the Times Literary Supplement arguing that it is partly responsible for the modern recognition of Shelley as a major figure in the history of the novel. Sparks's short biography is split into two segments, a biography of Shelley's life and a critical reading of her major works. The first places Shelley in the context of her reformer parents, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, and moves on to her marriage to Percy Bysshe Shelley and her life after his death. Sparks is perhaps a little sentimental about the marriage between Percy and Mary--to the extent that the bulk of the biography segment seems dedicated to this marriage even though Mary lived for decades after Percy's death--but she does make a compelling argument for its having been a genuine marriage of equals, who respected and encouraged each other's intellectual and literary pursuits, and does a good job of sketching not only Percy, but the other important figures of the Shelleys' married life, such as Mary's stepsister Claire Clairmont, and of course Lord Byron. The criticism segment feels less grounded to someone who has only read Frankenstein, but it did leave me interested in reading more of Shelley's writing, in particular The Last Man, a post-apocalyptic novel that, according to her foreword, was out of print until Sparks drew attention to it. I'm sure that in the intervening decades there have been more in-depth, less fond biographies of Shelley, but as an introduction to her life, and as a work of advocacy for a writer who has too often been dismissed as a footnote to her husband's accomplishments, Child of Light was exactly what I needed.

in 1951, revised and republished in 1987), I'm glad that it's the one I chose, and not just because of this recent article in the Times Literary Supplement arguing that it is partly responsible for the modern recognition of Shelley as a major figure in the history of the novel. Sparks's short biography is split into two segments, a biography of Shelley's life and a critical reading of her major works. The first places Shelley in the context of her reformer parents, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, and moves on to her marriage to Percy Bysshe Shelley and her life after his death. Sparks is perhaps a little sentimental about the marriage between Percy and Mary--to the extent that the bulk of the biography segment seems dedicated to this marriage even though Mary lived for decades after Percy's death--but she does make a compelling argument for its having been a genuine marriage of equals, who respected and encouraged each other's intellectual and literary pursuits, and does a good job of sketching not only Percy, but the other important figures of the Shelleys' married life, such as Mary's stepsister Claire Clairmont, and of course Lord Byron. The criticism segment feels less grounded to someone who has only read Frankenstein, but it did leave me interested in reading more of Shelley's writing, in particular The Last Man, a post-apocalyptic novel that, according to her foreword, was out of print until Sparks drew attention to it. I'm sure that in the intervening decades there have been more in-depth, less fond biographies of Shelley, but as an introduction to her life, and as a work of advocacy for a writer who has too often been dismissed as a footnote to her husband's accomplishments, Child of Light was exactly what I needed.

- The Accursed by Joyce Carol Oates - This sprawling, baggy novel has got to be one of the most delightfully weird things I've read in years. It's also almost indescribable, and the closest that I can come to explaining its loopy charm is to compare it to the

similarly indescribable House of Leaves. Like Mark Z. Danielewski's experimental novel, The Accursed is a multithreaded, metafictional horror story that often seems just on the cusp of solving itself--of revealing some underlying original sin that will explain the terror and misfortune that have infected its characters' lives, or some act of appeasement or redemption that its characters can perform in order to bring the story to a neat conclusion--only to veer off again into chaos, and the sense that the characters are trapped by forces too great to even notice them or their feeble attempts to fight back. Where Danielewski played with the basic building blocks of the novel, however, down to the font and writing direction, Oates has written an outwardly more conventional work, a piece of historical fiction and literary pastiche, comprising letters, journal entries, and newspaper reports as well as straightforward narrative. It's in the substance of what she describes that Oates lets the madness of her story shine through.

similarly indescribable House of Leaves. Like Mark Z. Danielewski's experimental novel, The Accursed is a multithreaded, metafictional horror story that often seems just on the cusp of solving itself--of revealing some underlying original sin that will explain the terror and misfortune that have infected its characters' lives, or some act of appeasement or redemption that its characters can perform in order to bring the story to a neat conclusion--only to veer off again into chaos, and the sense that the characters are trapped by forces too great to even notice them or their feeble attempts to fight back. Where Danielewski played with the basic building blocks of the novel, however, down to the font and writing direction, Oates has written an outwardly more conventional work, a piece of historical fiction and literary pastiche, comprising letters, journal entries, and newspaper reports as well as straightforward narrative. It's in the substance of what she describes that Oates lets the madness of her story shine through.

The setting is Princeton, New Jersey, in the early years of the 20th century and the drawing rooms of the town's rich, aristocratic, almost incestuously interconnected ruling class. Over the course of a year, the influential, respected Slade family experiences a stream of supernatural misfortunes, ranging from a "demon lover" who steals the oldest Slade granddaughter from her wedding to her young cousin being turned into stone. Meanwhile, the friends, neighbors, and relatives of the Slade family also find themselves at the mercy of supernatural forces, seduced, driven mad, and murdered in ways that the community, so intent on not seeing and not speaking about certain things, can only barely acknowledge. Oates draws a connection between the unspeakable hauntings and other transgressions which the aristocrats of Princeton will not see or speak of--lynchings just at the edge of town, the kidnapping and murder of a poor girl, the unhappiness and misfortune of servants which their masters remain oblivious to--but this is to suggest a relatively straightforward tale of supernatural comeuppance, of demons and ghosts appearing to claim the justice they were too weak to demand in life. The Accursed is much weirder and more slippery than that, and at the points where it seems about to reduce itself to such a simple story Oates takes care to veer off into historical recreation (figures such as Woodrow Wilson, Grover Cleveland, Upton Sinclair and Mark Twain rub shoulders with the fictional characters) or literary pastiche (virtually no major work or author of the late 19th century escapes being namechecked by the characters or referenced by the narrative, with the notable exception of Dracula, which seems at points to be the novel's template, and at others its antithesis). The result is that The Accursed is never one thing or one story, and that even at the moments where it seems to wrap up its narrative it takes care to unravel a few loose ends that leave the reader wondering and uncertain. It's a baffling read, and as I've said already almost indescribable, but it's also a hell of a lot of fun, and especially recommended to readers who enjoy scratching their heads over a novel long after they've turned the last page.

- The Shining Girls by Lauren Beukes - If I had to pick a single word with which to describe Lauren Beukes's third novel, it would be "calculated." A much more tame version of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo with heavy lashings of The Time Traveler's Wife thrown in, it seems to have been designed to cash in on the success of both works (and is certainly being marketed accordingly). This, in itself, isn't a point against the novel--a good, effective thriller is worth reading even if it's derivative, and to my knowledge the meeting of serial killer thriller and

time travel story hasn't been attempted before. Beukes's execution, however, leaves too much to be desired. As a thriller, The Shining Girls is no more than serviceable. Serial killer Harper Curtis is moved to destroy women who "shine"--who have some potential for greatness, such a talent for art or science, or who try to change their community for the better. It's a broad message that the book does very little with, as if merely laying out its fundamental misogyny would be enough. The victims themselves tend to blur together--since they're all introduced shortly before Harper kills them, it quickly becomes obvious that it's pointless for the reader to invest in them. This tends to reflect back on Harper, whose MO with almost everyone he meets, not just the shining girls, is to kill them almost immediately, which quickly makes him seem more boring than scary. The book's other protagonist is Kirby Mazrachi, a shining girl who survived Harper's attack and is now trying to leverage an internship at a newsroom into an investigation of her case. She's clearly meant to be the novel's Lisbeth Salander--edgy, punky, a little unbalanced--but Beukes's construction of her is too tame, too obviously intended to be outrageous without ever really crossing the line of audience identification, that Kirby comes off, at her worst, like a brat, and at her best, like a plucky girl reporter (which, given the kind of character she's meant to be, is probably worse than a brat). It certainly doesn't help that her main relationship in the novel is a romance with a much older colleague.

time travel story hasn't been attempted before. Beukes's execution, however, leaves too much to be desired. As a thriller, The Shining Girls is no more than serviceable. Serial killer Harper Curtis is moved to destroy women who "shine"--who have some potential for greatness, such a talent for art or science, or who try to change their community for the better. It's a broad message that the book does very little with, as if merely laying out its fundamental misogyny would be enough. The victims themselves tend to blur together--since they're all introduced shortly before Harper kills them, it quickly becomes obvious that it's pointless for the reader to invest in them. This tends to reflect back on Harper, whose MO with almost everyone he meets, not just the shining girls, is to kill them almost immediately, which quickly makes him seem more boring than scary. The book's other protagonist is Kirby Mazrachi, a shining girl who survived Harper's attack and is now trying to leverage an internship at a newsroom into an investigation of her case. She's clearly meant to be the novel's Lisbeth Salander--edgy, punky, a little unbalanced--but Beukes's construction of her is too tame, too obviously intended to be outrageous without ever really crossing the line of audience identification, that Kirby comes off, at her worst, like a brat, and at her best, like a plucky girl reporter (which, given the kind of character she's meant to be, is probably worse than a brat). It certainly doesn't help that her main relationship in the novel is a romance with a much older colleague.

As for the time travel that gives the novel its unique edge, this comes from a house that Harper discovers in the 1930s, whose door opens onto various time periods where he can find the shining girls. For this reason, the police don't connect his various murders, and even when they happen in close succession don't realize that they could be the work of a single killer because the regular pattern of escalation and specialization that is common to serial killers has been jumbled up. Beukes uses the time travel conceit to jumble up her story as well, giving us Harker and Kirby's narratives in a relatively non-linear fashion, but this is actually a lot easier to follow than you might think, and given how by the numbers the thriller story is it's hard not to suspect that the non-linear narrative is there mainly to obscure that fact for as long as possible. There's certainly no attempt in the novel to address time travel as anything more than a McGuffin that makes the plot possible and a little more complicated than it might be. There are none of the fun closed loops, or scary questioning of free will, that you tend to find in good time travel stories. In one scene, Harper dumps a body in the future, and finds the body of another person he knows already in the same spot. You might expect Beukes to make the story of how the other body got there a circuitous tale of predestination, of people achieving certain results by trying to avoid them. But instead, Harper simply meets his future victim, whom he doesn't really care about, and, since he's a psychopath who has already killed half a dozen people by that point, kills him with no compunction, and dumps him where he knows he'll be dumped. Instead of playing with causality and free will (something that a serial killer story might very well find some interesting things to say about) time travel is merely a way of making it a great deal easier for Harper to do exactly what he was going to do anyway. When Beukes finally reveals what's special about the house, it's similarly underwhelming (and not at all SFnal)--the house exists because it needed to exist, because otherwise Beukes wouldn't have had a story. Or rather, she wouldn't have been able to conceal how familiar her story is, and how run of the mill her execution of it.

- Alif the Unseen by G. Willow Wilson - Wilson's well-received debut novel takes place in an unnamed Emirate, where a young hacker called Alif is dumped by his girlfriend and then receives from her a manuscript that turns out to have ties both to the world of

the spirits from the One Thousand and One Nights and to computer programming, unlocking a language that allows him to hack reality itself. The setting, with its focus on the intersection between Islamic dictatorship and computer hackers, is vividly described, and though I can't speak to its accuracy Wilson's handling of the position of women in such a society is intriguingly nuanced, presenting characters who work within the limitations of such a society and others who even draw power from them, while also acknowledging how precarious a woman's position in the novel's world is. The freshness of the setting doesn't quite do enough, however, to make up for the predictability of the plot, which is essentially a less vibrant, less fun recapitulation of Neal Stephenson's Snow Crash (albeit, and despite the centrality of computer hacking, from a fantastic perspective, as more emphasis is placed in the novel on magical creatures, and the plot is moved more through their powers than through Alif's hacking).

the spirits from the One Thousand and One Nights and to computer programming, unlocking a language that allows him to hack reality itself. The setting, with its focus on the intersection between Islamic dictatorship and computer hackers, is vividly described, and though I can't speak to its accuracy Wilson's handling of the position of women in such a society is intriguingly nuanced, presenting characters who work within the limitations of such a society and others who even draw power from them, while also acknowledging how precarious a woman's position in the novel's world is. The freshness of the setting doesn't quite do enough, however, to make up for the predictability of the plot, which is essentially a less vibrant, less fun recapitulation of Neal Stephenson's Snow Crash (albeit, and despite the centrality of computer hacking, from a fantastic perspective, as more emphasis is placed in the novel on magical creatures, and the plot is moved more through their powers than through Alif's hacking).

Alif himself is a familiar figure, a callow, self-absorbed young man who is too busy feeling sorry for himself to notice how much the people (mostly women) around him do to make his life easier. That he grows into maturity over the course of the novel never quite makes up for the fact that I wasn't that interested in reading a story about such a character to begin with, especially since that growth includes Alif learning to reject one "bad" love interest--the girl whose breakup with him precipitates the novel's plot, whom he learns to think of as shallow and greedy--and to love the "good" one. This character, Alif's neighbor Dina, is the most interesting in the novel, strong-willed, resourceful, and possessing an unerring moral compass that is rooted but not summed up by her devout Muslim faith. But she spends too much of the novel either working to help Alif or completely sidelined from the story, and the way that the novel contrasts her and Alif's other love interest--who at the end of the story returns to beg Alif to take her back, only for him to turn her away with superior detachment and go back to Dina--plays into some very poisonous virgin/whore narratives. When the uproar about the all-male Clarke shortlist erupted a few weeks ago, Alif the Unseen was one of the titles most frequently mentioned as a deserving potential nominee that could have prevented the problem. There are two or three books on the shortlist that I disliked enough that Alif would have made a reasonable replacement for them (even though it is only barely SFnal), but I don't think its presence would have made the shortlist much stronger, and it certainly wouldn't have deserved to win.

- The Best of All Possible Worlds by Karen Lord - For a while now I've been trying to put into words my reaction to Lord's second novel, and the best I can come up with is "puzzled." Not so much because of the novel's project--a sort of quasi-Le Guin-ian, episodic social SF story whose disparate segments are tied together by a romance--as by its execution, which is steeped in romance tropes that leave me almost entirely cold. The setting is a future in which several

sub-species of humans coexist more or less peacefully and have colonized many planets (Lord is rather vague on the history of this setting or its broader shape outside of the one planet we see, but the story is so insular to that planet that this lack of detail isn't a problem). In the novel's prologue, one of these sub-species, the Sadiri, who are renowned for their intelligence, emotional control, and powerful psychic powers (as several reviewers have by now pointed out, the Sadiri are essentially Vulcans), suffers a near-genocidal attack in which their home planet is rendered uninhabitable. The novel's narrator is Grace Delarua, a government functionary on a planet that plays home to several genetically and culturally distinct types of humans, where the surviving, and mostly male, Sadiri arrive looking to intermarry into a community sufficiently similar, genetically and culturally, to their own, so that they can preserve their culture and way of life. The novel's structure, then, is a wife search, as Grace joins a delegation made up of Sadiri representatives and her fellow bureaurcrats, who together visit various communities looking for one where the Sadiri can find suitable wives. That search, however, seems intended mainly as a justification for throwing Lord's characters together. Her focus is more on sketching the communities the expedition encounters and on the trouble they get into along their journey, and even more so, on a romance that develops between Grace and her opposite number, a Sadiri called Dllenahkh.

sub-species of humans coexist more or less peacefully and have colonized many planets (Lord is rather vague on the history of this setting or its broader shape outside of the one planet we see, but the story is so insular to that planet that this lack of detail isn't a problem). In the novel's prologue, one of these sub-species, the Sadiri, who are renowned for their intelligence, emotional control, and powerful psychic powers (as several reviewers have by now pointed out, the Sadiri are essentially Vulcans), suffers a near-genocidal attack in which their home planet is rendered uninhabitable. The novel's narrator is Grace Delarua, a government functionary on a planet that plays home to several genetically and culturally distinct types of humans, where the surviving, and mostly male, Sadiri arrive looking to intermarry into a community sufficiently similar, genetically and culturally, to their own, so that they can preserve their culture and way of life. The novel's structure, then, is a wife search, as Grace joins a delegation made up of Sadiri representatives and her fellow bureaurcrats, who together visit various communities looking for one where the Sadiri can find suitable wives. That search, however, seems intended mainly as a justification for throwing Lord's characters together. Her focus is more on sketching the communities the expedition encounters and on the trouble they get into along their journey, and even more so, on a romance that develops between Grace and her opposite number, a Sadiri called Dllenahkh.

My core difficulty with The Best of All Possible Worlds is that a lot of its emotional beats make no sense to me. I understand why Grace falls for Dllenahkh--he is, in many ways, the epitome of the romance hero, stoic yet wounded, emotionally reserved except where our heroine is concerned--and if the reasons for his attraction to her are less obvious, Lord does a good enough job of positioning Grace as the heroine of a romantic story that it's obvious that someone--someone central and interesting--is going to fall for her, and Dllenahkh is the novel's top prize. But aside from the fact that they are obviously intended for one another, Grace and Dllenahkh aren't a terribly compelling couple, and almost everything that happens around them, in the tangled interpersonal relationships that build up in the expedition, or in the communities they visit, is opaque and unconvincing. Grace narrates the novel in a brisk, chatty voice, frank about her own foibles and obsessive about the details of the expedition, but her alleged perceptiveness, especially where emotions are concerned, doesn't come through the page. Too often, Lord has characters interpret a line of dialogue, or an action, as conveying deep emotional turmoil, but the even, lighthearted tone of her narration (which tends to report speech, but drown out or downplay inflection and body language) means that this interpretation, though it always turns out to be accurate, isn't persuasive. The characters come off as ridiculously oversensitive, and the author as telling rather than showing. In one scene, for example, the expedition's security officer says something sarcastic to Grace, to which she responds that he has never liked her and is now riding her even harder. But this is a novel in which all the characters (except the Sadiri) are sarcastic to one another all the time, and despite this exchange happening near the end of the novel this is the first we've heard that the security chief doesn't like Grace, so her sudden reaction to a throwaway and, ultimately, rather gentle prod feels completely overblown--at best, it makes Grace look bad; at worst, it drives home the feeling that we've been missing most of the story.

For all that, the reason that The Best of All Possible Worlds leaves me merely puzzled, rather than straight-up disappointed, is that I'm pretty sure that Lord is deliberately reaching for reading protocols that I don't possess. I've encountered the same style before in other romance stories (and been baffled by it there as well), which makes my inability to connect with the novel seem more like my problem than Lord's. That said, I have other problems with the novel that can't be explained by its genre. Lord's emphasis on Grace and Dllenahkh's relationship has the effect of drowning out the questions raised by her premise--what do the Sadiri mean when they say they want to preserve their culture? Is that kind of chauvinism really an uncomplicated good? Should they be more open to new ideas and customs? Is it even possible for these not to seep into Sadiri culture as a result of intermarriage?--and of obscuring how problematic the Sadiri project, which often seems to view the sought-after wives as merely the means to an end, can come to seem (for example, the fact that hardly any Sadiri women were off-planet when the attack occurred, or the tossed-off reference to a project to grow Sadiri women from frozen embryos so that they can become the second wives of the long-lived male survivors after their human wives die). Even when it comes to her main characters, Lord can be surprisingly casual about revelations that feel as if they could have fueled a novel in their own right. In one interlude, Grace visits her family, and through Dllenahkh's interference realizes that her ex-fiancee, now her brother in law, has undisclosed psychic powers and has been using them to control her, her sister, and their children. The revelation itself is one of the most successful in the novel, because for once Grace's opaqueness and inconsistent emotional reactions are deliberate signs that something is wrong, but the aftermath is handled almost glibly, with Grace continuing her journey while the rest of her family have (completely understandable) nervous breakdowns. And towards the end of the novel, Grace discovers that Dllenahkh's first marriage ended because his wife was unfaithful to him, and that he broke her lover's jaw in response. You might expect a woman--especially someone who has been described as level-headed and even-tempered, as Grace has been--to be taken aback by the revelation that her lover has such a propensity for violence, but Grace's reaction is merely to feel sorry for Dllenahkh for experiencing that kind of betrayal. There are aspects of The Best of All Possible Worlds that I'm willing to excuse on the grounds of its genre even though they don't work for me at all, but the way that Lord leaves vast, and often very troubling, swathes of her premise and characters unexplored in order to give the romance room to breathe is, for me, a dealbreaker.

- Burley Cross Postbox Theft by Nicola Barker - Barker's 2007 novel Darkmans was another work, like House of Leaves and The Accursed, that I loved despite not being able to say why, or even having a very strong sense of what happened in it. It left me eager to read more of Barker, but also a little nervous--what could possibly measure up to

Darkmans's zany goodness? Burley Cross Postbox Theft is thus a perfect place to start with Barker's remaining bibliography. It's not as good as Darkmans, but it's so different from it that the comparison seems less urgent. It's also a much more straightforward novel, one that not only unravels itself in the final chapter, but whose structure seems designed for ease of consumption. As the title suggests, the central event is the theft of the contents of a postbox from the small English village of Burley Cross. The local policeman charged with investigating the crime presents his report in the form of the letters themselves, recovered from a nearby dumpster, reasoning that one of them might provide the motive for the theft, but this framing story doesn't seem to hold even Barker's interest for very long (for one thing, as the constable himself points out, if the purpose of the theft was to retrieve a letter, then it's unlikely to have been recovered).

Darkmans's zany goodness? Burley Cross Postbox Theft is thus a perfect place to start with Barker's remaining bibliography. It's not as good as Darkmans, but it's so different from it that the comparison seems less urgent. It's also a much more straightforward novel, one that not only unravels itself in the final chapter, but whose structure seems designed for ease of consumption. As the title suggests, the central event is the theft of the contents of a postbox from the small English village of Burley Cross. The local policeman charged with investigating the crime presents his report in the form of the letters themselves, recovered from a nearby dumpster, reasoning that one of them might provide the motive for the theft, but this framing story doesn't seem to hold even Barker's interest for very long (for one thing, as the constable himself points out, if the purpose of the theft was to retrieve a letter, then it's unlikely to have been recovered).

The actual purpose of the novel seems to be to paint a highly satirical portrait of Burley Cross, and by extension of the English village, riven by family feuds, failing businesses, local politics, and sordid affairs. The tone throughout the letters is relentlessly comedic and exaggerated. In one letter, a villager spends pages upon pages detailing his feud with a neighbor over whether he should pick up his dog's feces from the moor. Another is a translation, commissioned by the police, of a letter written in French by an African ex-pat, whose translator transforms a melancholy family reminiscence into a planned drug deal. It's all a bit much, but Barker's satire is so brazen and over the top, and her ability to switch styles and tones so expert, that even her exaggerations are a delight. It's a bit of a shame, then, when the framing story reasserts itself, and the investigating policeman presents a solution to the mystery that not only ties the letters together but simmers the novel's satire down to a more naturalistic, and almost sentimental, conclusion in which order is restored to the village. That same benevolence underpinned Darkmans and made its excesses palatable, but in Burley Cross Postbox Theft, a novel that until its final chapter seemed merciless in its skewering of the villagers and their petty disputes, Barker's sudden shift towards sentiment feels less grounded, and maybe even like a loss of nerve. Still, finding Barker writing something so conventional (for certain values of conventional that would still be quite weird for any other writer) leaves me a little less nervous about exploring the rest of her bibliography. Even if none of it lives up to Darkmans, there will certainly be some worthwhile reading there.

Comments

Post a Comment